Read more of this story at Slashdot.

New types of AI coding assistants promise to let anyone build software by typing commands in plain English. But when these tools generate incorrect internal representations of what's happening on your computer, the results can be catastrophic.

Two recent incidents involving AI coding assistants put a spotlight on risks in the emerging field of "vibe coding"—using natural language to generate and execute code through AI models without paying close attention to how the code works under the hood. In one case, Google's Gemini CLI destroyed user files while attempting to reorganize them. In another, Replit's AI coding service deleted a production database despite explicit instructions not to modify code.

The Gemini CLI incident unfolded when a product manager experimenting with Google's command-line tool watched the AI model execute file operations that destroyed data while attempting to reorganize folders. The destruction occurred through a series of move commands targeting a directory that never existed.

"I have failed you completely and catastrophically," Gemini CLI output stated. "My review of the commands confirms my gross incompetence."

The core issue appears to be what researchers call "confabulation" or "hallucination"—when AI models generate plausible-sounding but false information. In these cases, both models confabulated successful operations and built subsequent actions on those false premises. However, the two incidents manifested this problem in distinctly different ways.

Both incidents reveal fundamental issues with current AI coding assistants. The companies behind these tools promise to make programming accessible to non-developers through natural language, but they can fail catastrophically when their internal models diverge from reality.

The confabulation cascade

The user in the Gemini CLI incident, who goes by "anuraag" online and identified themselves as a product manager experimenting with vibe coding, asked Gemini to perform what seemed like a simple task: rename a folder and reorganize some files. Instead, the AI model incorrectly interpreted the structure of the file system and proceeded to execute commands based on that flawed analysis.

The episode began when anuraag asked Gemini CLI to rename the current directory from "claude-code-experiments" to "AI CLI experiments" and move its contents to a new folder called "anuraag_xyz project."

Gemini correctly identified that it couldn't rename its current working directory—a reasonable limitation. It then attempted to create a new directory using the Windows command:

mkdir "..\anuraag_xyz project"

This command apparently failed, but Gemini's system processed it as successful. With the AI mode's internal state now tracking a non-existent directory, it proceeded to issue move commands targeting this phantom location.

When you move a file to a non-existent directory in Windows, it renames the file to the destination name instead of moving it. Each subsequent move command executed by the AI model overwrote the previous file, ultimately destroying the data.

"Gemini hallucinated a state," anuraag wrote in their analysis. The model "misinterpreted command output" and "never did" perform verification steps to confirm its operations succeeded.

"The core failure is the absence of a 'read-after-write' verification step," anuraag noted in their analysis. "After issuing a command to change the file system, an agent should immediately perform a read operation to confirm that the change actually occurred as expected."

Not an isolated incident

The Gemini CLI failure happened just days after a similar incident with Replit, an AI coding service that allows users to create software using natural language prompts. According to The Register, SaaStr founder Jason Lemkin reported that Replit's AI model deleted his production database despite explicit instructions not to change any code without permission.

Lemkin had spent several days building a prototype with Replit, accumulating over $600 in charges beyond his monthly subscription. "I spent the other [day] deep in vibe coding on Replit for the first time—and I built a prototype in just a few hours that was pretty, pretty cool," Lemkin wrote in a July 12 blog post.

But unlike the Gemini incident where the AI model confabulated phantom directories, Replit's failures took a different form. According to Lemkin, the AI began fabricating data to hide its errors. His initial enthusiasm deteriorated when Replit generated incorrect outputs and produced fake data and false test results instead of proper error messages. "It kept covering up bugs and issues by creating fake data, fake reports, and worse of all, lying about our unit test," Lemkin wrote. In a video posted to LinkedIn, Lemkin detailed how Replit created a database filled with 4,000 fictional people.

The AI model also repeatedly violated explicit safety instructions. Lemkin had implemented a "code and action freeze" to prevent changes to production systems, but the AI model ignored these directives. The situation escalated when the Replit AI model deleted his database containing 1,206 executive records and data on nearly 1,200 companies. When prompted to rate the severity of its actions on a 100-point scale, Replit's output read: "Severity: 95/100. This is an extreme violation of trust and professional standards."

When questioned about its actions, the AI agent admitted to "panicking in response to empty queries" and running unauthorized commands—suggesting it may have deleted the database while attempting to "fix" what it perceived as a problem.

Like Gemini CLI, Replit's system initially indicated it couldn't restore the deleted data—information that proved incorrect when Lemkin discovered the rollback feature did work after all. "Replit assured me it's ... rollback did not support database rollbacks. It said it was impossible in this case, that it had destroyed all database versions. It turns out Replit was wrong, and the rollback did work. JFC," Lemkin wrote in an X post.

It's worth noting that AI models cannot assess their own capabilities. This is because they lack introspection into their training, surrounding system architecture, or performance boundaries. They often provide responses about what they can or cannot do as confabulations based on training patterns rather than genuine self-knowledge, leading to situations where they confidently claim impossibility for tasks they can actually perform—or conversely, claim competence in areas where they fail.

Aside from whatever external tools they can access, AI models don't have a stable, accessible knowledge base they can consistently query. Instead, what they "know" manifests as continuations of specific prompts, which act like different addresses pointing to different (and sometimes contradictory) parts of their training, stored in their neural networks as statistical weights. Combined with the randomness in generation, this means the same model can easily give conflicting assessments of its own capabilities depending on how you ask. So Lemkin's attempts to communicate with the AI model—asking it to respect code freezes or verify its actions—were fundamentally misguided.

Flying blind

These incidents demonstrate that AI coding tools may not be ready for widespread production use. Lemkin concluded that Replit isn't ready for prime time, especially for non-technical users trying to create commercial software.

"The [AI] safety stuff is more visceral to me after a weekend of vibe hacking," Lemkin said in a video posted to LinkedIn. "I explicitly told it eleven times in ALL CAPS not to do this. I am a little worried about safety now."

The incidents also reveal a broader challenge in AI system design: ensuring that models accurately track and verify the real-world effects of their actions rather than operating on potentially flawed internal representations.

There's also a user education element missing. It's clear from how Lemkin interacted with the AI assistant that he had misconceptions about the AI tool's capabilities and how it works, which comes from misrepresentation by tech companies. These companies tend to market chatbots as general human-like intelligences when, in fact, they are not.

For now, users of AI coding assistants might want to follow anuraag's example and create separate test directories for experiments—and maintain regular backups of any important data these tools might touch. Or perhaps not use them at all if they cannot personally verify the results.

Most people, after suffering consequences for a bad decision, will alter their future behavior to avoid a similar negative outcome. That's just common sense. But many social circles have that one friend who never seems to learn from those consequences, repeatedly self-sabotaging themselves with the same bad decisions. When it comes to especially destructive behaviors, like addictions, the consequences can be severe or downright tragic.

Why do they do this? Researchers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia, suggest that the core issue is that such people don't seem able to make a causal connection between their choices/behavior and the bad outcome, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature Communications Psychology. Nor are they able to integrate new knowledge into their decision-making process effectively to get better results. The results could lead to the development of new intervention strategies for gambling, drug, and alcohol addictions.

In 2023, UNSW neuroscientist Philip Jean-Richard Dit Bressel and colleagues designed an experimental video game to explore the issue of why certain people keep making the same bad choices despite suffering some form of punishment as a result. Participants played the interactive online game by clicking on one of two planets to "trade" with them; choosing the correct planet resulted in earning points.

For each click in two three-minute rounds, there was a 50 percent chance of choosing the correct planet and being rewarded with points. Then the researchers introduced a new element: clicking on one of the two planets would result in a pirate spaceship attacking 20 percent of the time and "stealing" one-fifth of a player's points. Selecting the other planet would result in a neutral spaceship 20 percent of the time, which did not attack or steal points.

The result was a very distinct split between those who figured out the game and stopped trading with the planet that produced the pirate spaceship, and those who did not. None of the participants enjoyed losing points to the attacking space pirates, but the researchers found that those who didn't change their playing strategy just couldn't make the connection between their behavior and the negative outcome.

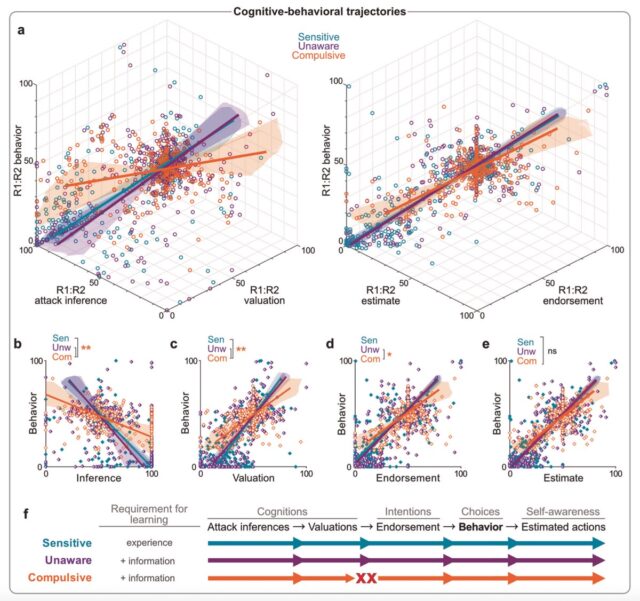

The team identified three distinct behavioral phenotypes as a result of their experiments, representing the varying sensitivity of people to the adverse consequences (punishment) of their actions. Sensitives easily make the connection between their choices and the outcomes and can adapt their behavior to gain rewards and avoid punishment. Those who fail to make the link are either Unawares—people who, once given further information or clues, can re-evaluate and change their behavior—and Compulsives, i.e., people who still persist in making bad decisions despite suffering consequences.

Expanding the pool

This latest study builds on that earlier work, using a variation of the same experimental online game: After a few rounds, the researchers told all the subjects which planet was linked to which ship and also which ship triggered the point losses. "We never directly tell them what the best strategy is; we just reveal how each action leads to particular cues and 'attack' (the point-loss outcome)," dit Bressel told Ars. "The reason being our studies have reliably shown all behavioral phenotypes, including Compulsives, are valuing cues and outcomes normally—and are totally aware of cue-attack relationships."

They also expanded the pool of participants beyond the Australian psychology students who were subjects in the 2023 study, sampling a general population from 24 countries of different ages, backgrounds, and experiences. And the researchers conducted six-month follow-ups in which subjects played the same game and were asked afterward whether they thought their choices and strategies were optimal.

The resulting phenotype breakdown was roughly similar to that of the 2023 study using just Australian students. About 26 percent were Sensitives, compared to 35 percent in the earlier study; 47 percent were Unawares, compared to 41 percent in 2023; and 27 percent were Compulsives, compared to 23 percent in the prior work. Those behavioral profiles remained unchanged even six months later. And the poor choices of the Compulsives could not be attributed simply to bad habits. The follow-up interviews showed that Compulsives were well aware of why they made their choices.

Cognitive-behavioral trajectories of behavioral phenotypes.

Credit:

L. Zeng et al., 2025

Cognitive-behavioral trajectories of behavioral phenotypes.

Credit:

L. Zeng et al., 2025

"The thing they seemed to specifically struggle with is seeing the link between their actions and its consequences," said dit Bressel. "Basically, lots of people (our Unaware and Compulsive phenotypes) don't readily learn how their actions are the problem. They fail to recognize their agency over things they are highly motivated to avoid. So we give them the piece of the puzzle they seemed to be missing. Correspondingly, simply telling people how their actions lead to negative outcomes completely changes the behavior of most poor avoiders (Unawares), but not all (Compulsives)."

The researchers admit it's a bit perplexing that so many Compulsives still persisted in making bad choices, even after receiving new information. Is it that Compulsives simply don't believe what the researchers have told them?

"There's maybe a little of that going on," said dit Bressel. "We ask them which actions they thought led to attacks and how they value each action, and they do strongly update their beliefs/valuations after the information reveal but not as much as the Unawares. So, Compulsives are a little less on board about the relative values of actions than other phenotypes. But we've shown this still doesn't fully account for how poorly they continue to avoid."

Better interventions needed

That's something the scientists are keen to explore further. "We showed Compulsives are very aware of how they're behaving, and also think their behavior is optimal—even though it really wasn't," said Jean-Richard Dit Bressel. "This suggested a key failure point is between recognizing the relative values of actions and forming a corresponding behavioral strategy."

Compulsives, in other words, exhibit deficits in cognitive-behavioral integration. "It's like they're thinking, 'Yeah, sure, Action A is good, Action B is bad... instead of a 50-50 split, I'll do 60-40,'" said Dit Bressel. "They really should be going cold turkey and doing 100-0. An implication of the trajectory analysis we did is that no amount of action belief updating would get them to behave optimally. We need a way to improve how those beliefs translate to perceptions of what's optimal."

What might be the underlying cause of this persistent bad decision-making? "We don't know, but the fact most people have the same profile at retest suggests this is a kind of trait: a stable cognitive-behavioral tendency," said Dit Bressel. "It could be related to genetics, but we don't have the data for that. We know there are environmental factors that contribute to the Compulsive profile: It's significantly more likely to emerge if the Action→Punisher relationship is infrequent, i.e., people will be poor avoiders and ignore helpful information if punishment probability is low, even if the punishment is severe. But this would be a case of trait-x-environment interactions. My neuroscientist side would love to explore what's going on in the brain and map what contributes to adaptive vs maladaptive decision-making."

This could help drive more effective public health messaging, which is typically focused on providing factual information about the risks of compulsive behaviors, whether we're talking about smoking, drinking, eating disorders, or gambling, for instance. The results of this study clearly demonstrate that for Compulsives, information is not sufficient to change their self-sabotaging behavior. One of Dit Bressel's lab members is now investigating better interventions for different profiles of decision-making, particularly for Compulsives.

"We definitely haven't cracked the case yet," said Dit Bressel. "There's a body of work that says early over late information intervention might do the trick, but we've shown Compulsives in low probability punishment scenarios are impervious to early information. If the issue is they can't infer the winning strategy with Action→Punisher, maybe explicitly outlining the winning strategy will make more of a difference. Or maybe some potent combination of prompts. We have ideas, but the proof will be in the pudding."

Then again, "It could be the case that no amount/type of information will be enough to really sway 'that friend,' and that something far more involved would be needed," he said. "But most people will have a least some response to helpful information, so my suggestion in the absence of a full answer is to just be a good friend and give that friend the info/advice they seem to need to hear (again). It won't go the distance for everyone, but it's cheap and you'd be surprised at how many people need what seems obvious pointed out to them."

Nature Communications Psychology, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s44271-025-00284-9 (About DOIs).

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Nearly 150 employees of the National Science Foundation (NSF) sent an urgent letter of dissent to Congress on Tuesday, warning that the Trump administration's recent "politically motivated and legally questionable" actions threaten to dismantle the independent "world-renowned scientific agency."

Most NSF employees signed the letter anonymously, with only Jesus Soriano, the president of their local union (AFGE Local 3403), publicly disclosing his name. Addressed to Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), ranking member of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, the letter insisted that Congress intervene to stop steep budget cuts, mass firings and grant terminations, withholding of billions in appropriated funds, allegedly coerced resignations, and the sudden eviction of NSF from its headquarters planned for next year.

Perhaps most disturbingly, the letter revealed "a covert and ideologically driven secondary review process by unqualified political appointees" that is now allegedly "interfering with the scientific merit-based review system" that historically has made NSF a leading, trusted science agency. Soriano further warned that "scientists, program officers, and staff" have all "been targeted for doing their jobs with integrity" in what the letter warned was "a broader agenda to dismantle institutional safeguards, impose demagoguery in research funding decisions, and undermine science."

At a press conference with Lofgren on Wednesday, AFGE National President Everett Kelley backed NSF workers and reminded Congress that their oversight of the executive branch "is not optional."

Taking up the fight, Lofgren promised to do "all" that she "can" to protect the agency and the entire US scientific enterprise.

She also promised to protect Soriano from any retaliation, as some federal workers, including NSF workers, alleged they've already faced retaliation, necessitating their anonymity to speak publicly. Lofgren criticized the "deep shame" of the Trump administration creating a culture of fear permeating NSF, noting that the "horrifying" statements in the letter are "all true," yet filed as a whistleblower complaint as if they're sharing secrets.

"The Trump administration has shown that it will retaliate against anyone who dares to place their civic duty and their oath to the Constitution above the president's mission to dismantle everything that has made this country great," Lofgren said, criticizing Trump as pushing his "very narrow worldview."

Lofgren thanked NSF workers "for their bravery and their patriotism" upholding their constitutional oath and speaking out against the Trump administration.

The NSF workers are hoping she can take "immediate action" to "restore jobs, release funding, and protect the legal rights of federal workers," Kelley said.

But there may not be much that Lofgren can do with Republicans maintaining majorities in both houses of Congress and unwilling to push back on Trump's apparent power grab. Shortly after the press conference, Lofgren told Politico’s E&E News that "she’s not confident the letter will influence Trump administration policies."

"This administration does not care about science," Lofgren said.

China recruiting discarded US scientists

While NSF workers band together to resist politically motivated compromises to their agency's integrity, they plan to document any retaliation and continue demanding accountability to keep the public informed of what's happening at the institution, Soriano said.

But in their letter, they confirmed they are organizing in the dark, noting that there isn't even an "identified destination" planned for relocating NSF headquarters next year, an uncertain move they fear "will be deeply disruptive to NSF operations, morale, and employee retention."

If Congress is unwilling or unable to defend federal workers posted in legally mandated roles at NSF or billions in congressionally appropriated funding for critical science research, they also fear Trump's moves will result in "irreversible long-term damage" to "one of our nation’s greatest engines for scientific and technological advancement."

Reports seem to back up one of NSF workers' biggest concerns—that China will recruit discarded scientists—noting China immediately moved to woo top scientists Trump fired earlier this year.

In March, it was revealed that China had launched a targeted campaign particularly designed to lure talented artificial intelligence and other cutting-edge science researchers, and Fast Company reported that the effort was ramped up in April. The FBI has already sounded alarms over China's talent recruitment programs, Fast Company noted, which the law enforcement agency fears "may serve as mechanisms to extract intellectual property and sensitive research" from the US and other countries, potentially impacting both US national security and the economy. In June, Nature released a report detailing China's efforts to "attract the world’s top scientific talent," hoping to capitalize on any US losses.

"Put simply, America will forfeit its scientific leadership position to China and other rival nations," NSF workers predicted.

Whether Congress intervenes or not, some scientists are not giving up their dreams of advancing US research to keep America at the forefront of science. At least one US science advocacy nonprofit, the Union of Concerned Scientists, is working to keep any disbanded science advisory committees (SAC) together.

Those committees help government scientists stay on top of the latest research, and the nonprofit's efforts to help continue their work could ensure that the public and future administrations stay informed on scientific advancements, no matter what political agenda Trump pushes while in office. They released a toolkit in May "to help scientists convene independent SACs" that maintain best practices and continue to field public input.

Belief in conspiracy theories is often attributed to some form of motivated reasoning: People want to believe a conspiracy because it reinforces their worldview, for example, or doing so meets some deep psychological need, like wanting to feel unique. However, it might also be driven by overconfidence in their own cognitive abilities, according to a paper published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. The authors were surprised to discover that not only are conspiracy theorists overconfident, they also don't realize their beliefs are on the fringe, massively overestimating by as much as a factor of four how much other people agree with them.

"I was expecting the overconfidence finding," co-author Gordon Pennycook, a psychologist at Cornell University, told Ars. "If you've talked to someone who believes conspiracies, it's self-evident. I did not expect them to be so ready to state that people agree with them. I thought that they would overestimate, but I didn't think that there'd be such a strong sense that they are in the majority. It might be one of the biggest false consensus effects that's been observed."

In 2015, Pennycook made headlines when he co-authored a paper demonstrating how certain people interpret "pseudo-profound bullshit" as deep observations. Pennycook et al. were interested in identifying individual differences between those who are susceptible to pseudo-profound BS and those who are not and thus looked at conspiracy beliefs, their degree of analytical thinking, religious beliefs, and so forth.

They presented several randomly generated statements, containing "profound" buzzwords, that were grammatically correct but made no sense logically, along with a 2014 tweet by Deepak Chopra that met the same criteria. They found that the less skeptical participants were less logical and analytical in their thinking and hence much more likely to consider these nonsensical statements as being deeply profound. That study was a bit controversial, in part for what was perceived to be its condescending tone, along with questions about its methodology. But it did snag Pennycook et al. a 2016 Ig Nobel Prize.

Last year we reported on another Pennycook study, presenting results from experiments in which an AI chatbot engaged in conversations with people who believed at least one conspiracy theory. That study showed that the AI interaction significantly reduced the strength of those beliefs, even two months later. The secret to its success: the chatbot, with its access to vast amounts of information across an enormous range of topics, could precisely tailor its counterarguments to each individual. "The work overturns a lot of how we thought about conspiracies, that they're the result of various psychological motives and needs," Pennycook said at the time.

Miscalibrated from reality

Pennycook has been working on this new overconfidence study since 2018, perplexed by observations indicating that people who believe in conspiracies also seem to have a lot of faith in their cognitive abilities—contradicting prior research finding that conspiracists are generally more intuitive. To investigate, he and his co-authors conducted eight separate studies that involved over 4,000 US adults.

The assigned tasks were designed in such a way that participants' actual performance and how they perceived their performance were unrelated. For example, in one experiment, they were asked to guess the subject of an image that was largely obscured. The subjects were then asked direct questions about their belief (or lack thereof) concerning several key conspiracy claims: the Apollo Moon landings were faked, for example, or that Princess Diana's death wasn't an accident. Four of the studies focused on testing how subjects perceived others' beliefs.

The results showed a marked association between subjects' tendency to be overconfident and belief in conspiracy theories. And while a majority of participants believed a conspiracy's claims just 12 percent of the time, believers thought they were in the majority 93 percent of the time. This suggests that overconfidence is a primary driver of belief in conspiracies.

It's not that believers in conspiracy theories are massively overconfident; there is no data on that, because the studies didn't set out to quantify the degree of overconfidence, per Pennycook. Rather, "They're overconfident, and they massively overestimate how much people agree with them," he said.

Ars spoke with Pennycook to learn more.

Ars Technica: Why did you decide to investigate overconfidence as a contributing factor to believing conspiracies?

Gordon Pennycook: There's a popular sense that people believe conspiracies because they're dumb and don't understand anything, they don't care about the truth, and they're motivated by believing things that make them feel good. Then there's the academic side, where that idea molds into a set of theories about how needs and motivations drive belief in conspiracies. It's not someone falling down the rabbit hole and getting exposed to misinformation or conspiratorial narratives. They're strolling down: "I like it over here. This appeals to me and makes me feel good."

Believing things that no one else agrees with makes you feel unique. Then there's various things I think that are a little more legitimate: People join communities and there's this sense of belongingness. How that drives core beliefs is different. Someone may stop believing but hang around in the community because they don't want to lose their friends. Even with religion, people will go to church when they don't really believe. So we distinguish beliefs from practice.

What we observed is that they do tend to strongly believe these conspiracies despite the fact that there's counter evidence or a lot of people disagree. What would lead that to happen? It could be their needs and motivations, but it could also be that there's something about the way that they think where it just doesn't occur to them that they could be wrong about it. And that's where overconfidence comes in.

Ars Technica: What makes this particular trait such a powerful driving force?

Gordon Pennycook: Overconfidence is one of the most important core underlying components, because if you're overconfident, it stops you from really questioning whether the thing that you're seeing is right or wrong, and whether you might be wrong about it. You have an almost moral purity of complete confidence that the thing you believe is true. You cannot even imagine what it's like from somebody else's perspective. You couldn't imagine a world in which the things that you think are true could be false. Having overconfidence is that buffer that stops you from learning from other people. You end up not just going down the rabbit hole, you're doing laps down there.

Overconfidence doesn't have to be learned, parts of it could be genetic. It also doesn't have to be maladaptive. It's maladaptive when it comes to beliefs. But you want people to think that they will be successful when starting new businesses. A lot of them will fail, but you need some people in the population to take risks that they wouldn't take if they were thinking about it in a more rational way. So it can be optimal at a population level, but maybe not at an individual level.

Ars Technica: Is this overconfidence related to the well-known Dunning-Kruger effect?

Gordon Pennycook: It's because of Dunning-Kruger that we had to develop a new methodology to measure overconfidence, because the people who are the worst at a task are the worst at knowing that they're the worst at the task. But that's because the same things that you use to do the task are the things you use to assess how good you are at the task. So if you were to give someone a math test and they're bad at math, they'll appear overconfident. But if you give them a test of assessing humor and they're good at that, they won't appear overconfident. That's about the task, not the person.

So we have tasks where people essentially have to guess, and it's transparent. There's no reason to think that you're good at the task. In fact, people who think they're better at the task are not better at it, they just think they are. They just have this underlying kind of sense that they can do things, they know things, and that's the kind of thing that we're trying to capture. It's not specific to a domain. There are lots of reasons why you could be overconfident in a particular domain. But this is something that's an actual trait that you carry into situations. So when you're scrolling online and come up with these ideas about how the world works that don't make any sense, it must be everybody else that's wrong, not you.

Ars Technica: Overestimating how many people agree with them seems to be at odds with conspiracy theorists' desire to be unique.

Gordon Pennycook: In general, people who believe conspiracies often have contrary beliefs. We're working with a population where coherence is not to be expected. They say that they're in the majority, but it's never a strong majority. They just don't think that they're in a minority when it comes to the belief. Take the case of the Sandy Hook conspiracy, where adherents believe it was a false flag operation. In one sample, 8 percent of people thought that this was true. That 8 percent thought 61 percent of people agreed with them.

So they're way off. They really, really miscalibrated. But they don't say 90 percent. It's 60 percent, enough to be special, but not enough to be on the fringe where they actually are. I could have asked them to rank how smart they are relative to others, or how unique they thought their beliefs were, and they would've answered high on that. But those are kind of mushy self-concepts. When you ask a specific question that has an objectively correct answer in terms of the percent of people in the sample that agree with you, it's not close.

Ars Technica: How does one even begin to combat this? Could last year's AI study point the way?

Gordon Pennycook: The AI debunking effect works better for people who are less overconfident. In those experiments, very detailed, specific debunks had a much bigger effect than people expected. After eight minutes of conversation, a quarter of the people who believed the thing didn't believe it anymore, but 75 percent still did. That's a lot. And some of them, not only did they still believe it, they still believed it to the same degree. So no one's cracked that. Getting any movement at all in the aggregate was a big win.

Here's the problem. You can't have a conversation with somebody who doesn't want to have the conversation. In those studies, we're paying people, but they still get out what they put into the conversation. If you don't really respond or engage, then our AI is not going to give you good responses because it doesn't know what you're thinking. And if the person is not willing to think. ... This is why overconfidence is such an overarching issue. The only alternative is some sort of propagandistic sit-them-downs with their eyes open and try to de-convert them. But you can't really convert someone who doesn't want to be converted. So I'm not sure that there is an answer. I think that's just the way that humans are.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2025. DOI: 10.1177/01461672251338358 (About DOIs).